The History of Bricks, Part 2

‘The problem of architecture as I see it is the problem of all art – the elimination of the human element from the consideration of the form.’

Evelyn Waugh, Decline and Fall

In Part 1 of our brief canter through the story of bricks through the ages – https://www.turnerandhoskins.co.uk/the-history-of-bricks-part-1/ – we stopped at a pivotal moment in history, just before the first brickmaking machines were introduced.

Rise in demand for bricks in the 19th century

The population of Britain increased exponentially in the first half of the 19th century. Add to this the fact that large numbers of agricultural workers moved to urban centres in search of better employment opportunities, creating an unprecedented need for houses. Concurrently, a huge boom in the textile industries of Yorkshire and Lancashire resulted in the construction of many mills and factories in the 1820s. Without bricks, in areas with insufficient supply of stone, this building boom would have been unsustainable—and such enormous quantities of bricks were required that making them by hand was no longer viable. Additionally, the supply of superior quality pure clay was all but exhausted close to cities, so some process had to be devised to allow the use of inferior mixtures of material.

Left: The development of the Railways placed a huge demand on the requirement for the manufacture of bricks; Queens Road, Battersea

Right: Detail showing Mathematical Tiles, Lewes, East Sussex. Designed to give the appearance of bricks, many buildings in Lewes employed the use of mathematical tiles to avoid the brick tax.

Another factor to take into consideration was a tax on bricks and tiles, imposed by William Pitt in 1784, to repay debts incurred during the American War of Independence. Of course, this meant that the price of bricks increased dramatically, at the very time when bricks were in greater demand. Not such good news if it priced brickmakers out of the market, so cost-reducing technological solutions became an imperative.

Social history and bricks

In order to produce more bricks more quickly, skilled brickmakers were forced to cut corners and shoddy workmanship was the result, exacerbated by the deplorable conditions endured by the workforce.

‘Frequently have our hearts bled to see the degrading labour to which the brickfield has subjected our species, and most revolting of all to see women put to the drudgery of horses and engines; little children too, who in a country like this should be at school, disguised past recognition in the mixed sweat and plasterings of clay and mud which encumbered their attenuated frames…’ (The Builder 1843, p. 193).

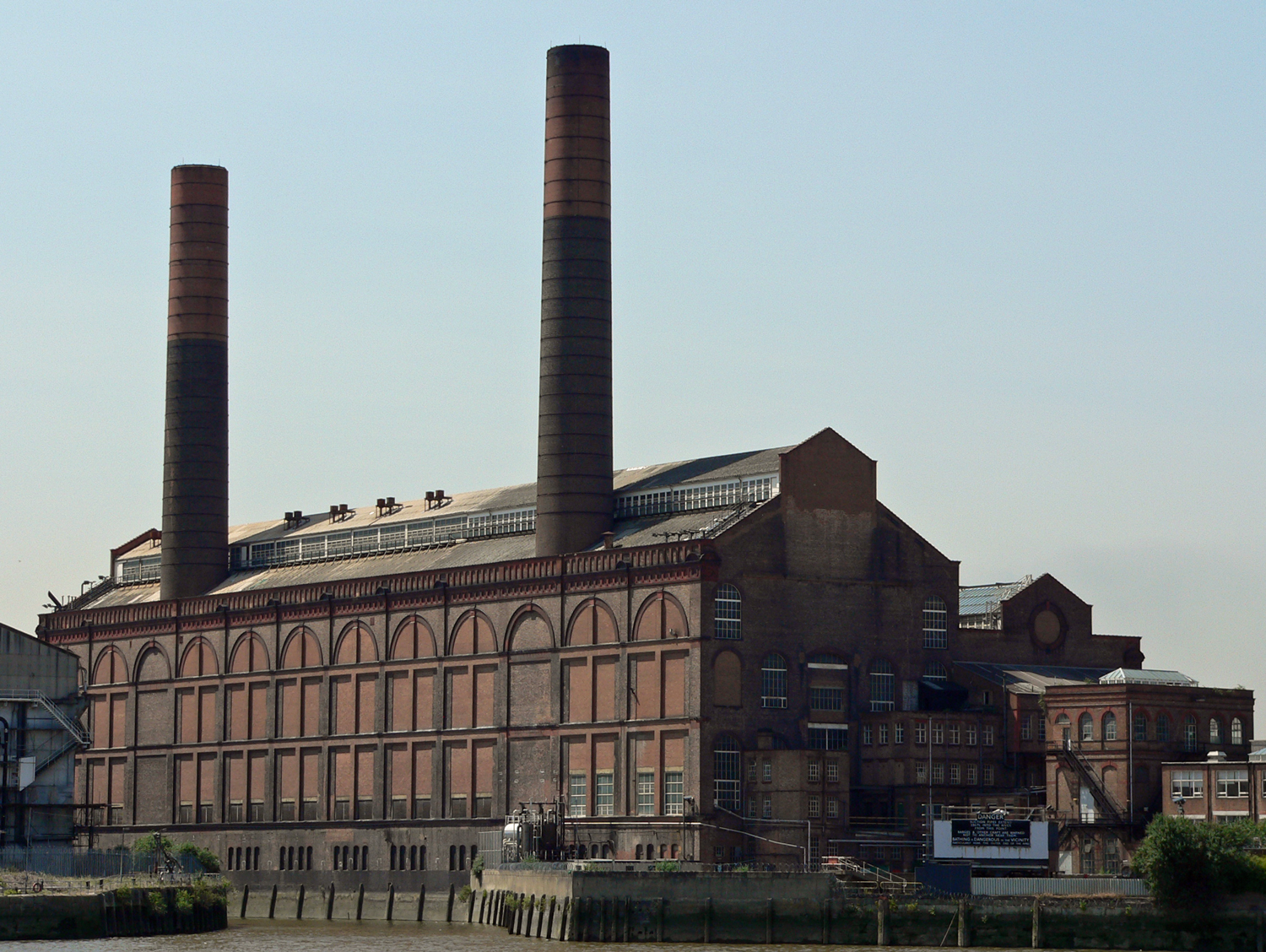

Lots Road Power Station, London

In addition, there was an upsurge in industrial disputes amongst the brickmaking workforce, usually set off when traditional work practices were challenged, despite the demonstrable iniquity of the trade. This, somewhat ironically, provided a greater incentive for replacing human beings with labour-saving mechanical devices.

The mechanisation of brickmaking

As early as 1741, the first patent for a Brick and Tile Making Machine was presented by one William Bailey of Taunton. He claimed:

‘the whole work may be completed without touching the clay with the hands or feet of the labourers, and any person may be fully instructed in half an hour to work the engine…’

By 1850 a further 131 patents are recorded, all to do with speeding up the moulding of bricks. It was hoped that these innovations would restore dignity and some degree of moral integrity to the industry, as well as being cost-effective in providing stronger bricks of a more uniform and better quality.

Pressing machines replaced the laborious hand process of finishing bricks once beaten with a wedge-shaped tool known as a dresser. Improvements were made to kilns and drying sheds—for instance, tunnel kilns were developed where bricks were stacked on kiln cars and pushed through a long tube, to emerge, fully-fired at the other end.

Today, the processes are much the same, with variations and further modernisation. There are enormous high-tech factories with fully automated processes capable of producing millions of perfectly formed bricks, quickly and efficiently.

There’s a comprehensive overview from the Brick Development Association here, if you’d like to be a real brick aficionado http://www.brick.org.uk/admin/resources/g-the-uk-clay-brickmaking-process.pdf

Left: Checking the quality of bricks during firing.

Much to our relief, handmade bricks maintain a place in the modern market. The need to complement historic brickwork demands the production of bricks with individual character in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. They are an important link to the past, enhancing today’s buildings and contributing to the architectural landscape of the future.

Modern brickworks: Ibstock Bricks, South Holmwood Factory

Bricks at Turner and Hoskins Architects

Our clients very often want a certain look or style to their building. Choosing the right brick is fundamental to achieving their wishes. It’s part of the process that we, as architects with a passion for bricks, take time to research and delight in the outcome.

The clients for this project wanted a Victorian Industrial aesthetic, so that it felt like a converted industrial building. The use of brick internally was crucial to complete the look.

The clients for this project wanted a Victorian Industrial aesthetic, so that it felt like a converted industrial building. The use of brick internally was crucial to complete the look.

https://www.turnerandhoskins.co.uk/portfolio/the-bookcase-door/

These clients for this project wanted a loft-style ambience:

These clients for this project wanted a loft-style ambience:

https://www.turnerandhoskins.co.uk/little-metal-tardis/

This project included a side extension, so matching the existing bricks was therefore very important. We spent a good deal of time sourcing the right ones:

This project included a side extension, so matching the existing bricks was therefore very important. We spent a good deal of time sourcing the right ones:

https://www.turnerandhoskins.co.uk/portfolio/doubling-up/

And with this one, in South London, we needed to source a brick like the south London stock brick, and chose one with warmth and character, which is used a lot externally, but also internally within the main hall:

And with this one, in South London, we needed to source a brick like the south London stock brick, and chose one with warmth and character, which is used a lot externally, but also internally within the main hall:

https://www.turnerandhoskins.co.uk/portfolio/woodside-green-christian-centre/