Recognising the need: ergonomics and anthropometrics in architectural design

‘Recognising the need is the primary condition for design,’

Charles Eames

Here at Turner & Hoskins, that’s a philosophy which truly resonates with us since everything we do is about designing for specific people and their comfort.

Ergonomics and anthropometrics are the highly technical methodologies which lie behind what we strive to achieve – creating living and working spaces which fit the needs of their inhabitants.

Ergonomics

There’s science as well as art in architecture. Ergonomics is a scientific discipline which studies human abilities and limitations and applies this learning to improve people’s interaction with products and environments. We’ve all heard about ergonomics in relation to office furniture and other (allegedly) posture-improving accessories, but the science equally applies to building design

It has interesting origins: in 1949, a working party was set up to look at human beings at work. During the Second World War, academics in the fields of engineering, medicine and the human sciences had been engaged in research aimed at improving the efficiency of the fighting man. It was thought that it would be possible to develop the concepts for peacetime purposes, particularly with reference to workplaces.

If a workplace isn’t well-designed to maximise user-comfort and efficiency, it’s been shown to result in lower productivity, more absenteeism due to illness, plummeting staff morale and motivation and increased staff turnover. To illustrate it simply, office desks are made to a standard height; office workers are not.

In domestic and community environments, which occupy most of our time at Turner & Hoskins, the same principles apply, in a personal rather than commercial sense.

‘Design is not just what it looks like…design is how it works.’

Steve Jobs

How do we measure human abilities and limitations?

That’s where anthropometrics comes in. All you Greek scholars will know that the word derives from anthropos (human), and metron (measure). Measuring the dimensions and capabilities of the human body allows designers – architects like us – to adapt buildings to fit people rather than requiring people to adapt to buildings.

No need to panic. If you take us on to design your house, we won’t be arriving on your doorstep with a tape measure to calculate your body dimensions! There is ample anthropometric data out there, regularly updated to reflect changes in the population.

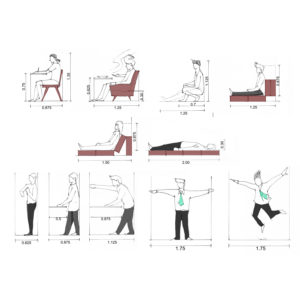

Anthropometry falls into two main strands:

- Static – the measurement of body sizes at rest

- Functional – the measurement of the body’s ability to complete tasks, reaching, moving, interacting with spaces

While average measurements are useful, and building regulations provide standard requirements, we’re always mindful that one size certainly doesn’t fit all. People with mobility issues, wheelchair users, the very young and the considerably older may have specific requirements which we will take into account. Good accessibility and ease of manoeuvring around the building inform our thoughts about room sizes, corridors and corners, stairways, and lifts and ramps if necessary.

‘A house is a machine for living in.’

Le Corbusier

This is what we will never be

We will never be procrustean. In Greek mythology, Procrustes, son of Poseidon and rogue bandit, had an iron bed on to which he tied his captives. If they were too short, he stretched them to make them fit. If they were too tall, he lopped bits off their limbs.

The word procrustean describes circumstances where different sizes and properties are fitted to an arbitrary standard.

That’s not we do with our building design or the people for whom we design.

‘Form and function should be one.’

Frank Lloyd Wright